Podcast Ep.5 Heads In The Clouds

Our smart phones would be pretty dumb without cloud connectivity. Just how clean and green is this 'cloud' that powers our digital lives?

Everything comes from everywhere: globalisation, enmeshed with anaemic policy, constrains effective climate and overshoot action. But times are changing. Will strained to breaking point supply chains and resource nationalism mean we will need to prioritise what we ask of the rest of the world?

The first few posts of this blog sketch some issues that will impact our lives over the next couple of decades and give some sense of their magnitude. Not the lightest reading I know. I will soon be turning to discussions about what we can and perhaps should be doing to mitigate and respond to these impacts. However, it is important to first highlight a critical constraint upon our ability to act effectively, as either individuals or collectively, to change the current trajectory of overshoot and climate impacts.

Put simply, we are enmeshed in a level of civilisational complexity that will make it very hard to change.

The most obvious way in which we are enmeshed is within globalised supply chains for almost every single good or service we want or need today; or will want or need to respond to the overshoot and climate challenges of the next couple of decades. Taking just a couple of examples from our daily lives, it is clear that everything comes from everywhere.

Take something as simple as frozen crumbed sardines. Caught off the south-west Australian coast near where I live, they find their way to my plate having first travelled to Thailand to be crumbed with a mixture of breadcrumbs containing wheat flour from either North America or Eastern Australia and palm oil from Indonesia, then packaged in plastics produced in China. All these ingredients, including the sardines, being shipped by the burning of fossil fuels extracted in the Middle East. The cooking oil used on the European manufactured frypan (made from metals extracted from ores in Brazil) to fry the sardines having come from Spain via Italy. The condiments beside my plate: pepper from Sri Lanka, salt from closer to home, the north-west Australian coast (albeit delivered in packaging made in China from fossil fuel products - again from the Middle East). Only the slice of lemon is from a locally grown tree.

And that is just a simple foodstuff. When we think of more complex goods and services, the everything from everywhere principal compounds exponentially. Smartphones and the apps and services we access via these devices rely not only on mineral resources from pretty much every continent except Antarctica, but technical expertise, manufacturing equipment, human labour and computer server rooms spread across multiple continents.

Things like smartphone devices and mobile apps are evolving at a very rapid rate; rendering these highly complex offerings obsolete within five years. Both we as consumers and the commercial suppliers of these and other high technology goods and services increasingly recognise this. As a consequence, we are no longer buying high tech goods and services outright. Instead we are becoming increasingly enmeshed in leasing or subscription/consumption models of contracting. If we stop paying the subscriptions, even if we have a physical device in our hand, our favourite app or most important memories stored in the cloud will no longer be accessible to us.

An insidious corollary in which we are enmeshed is the loss of ownership of the right to consume and enjoy many forms of original intellectual property, such as music or books, following a one-time purchase. As we are enticed to subscribe to all-you-can-eat books, video, podcasts and music offerings, we are losing the right of independent ownership of an unrestricted copy of the songs and books and the right to informally share these with our friends, colleagues and family. I am not suggesting a return to Napster, which harmed the creators of this intellectual property. On the other side of the creative fence we also need to ask: are the subscriptions platforms offering artists a fair deal?

This loss of ownership is also expressed in the loss of right of repair. From smartphones to tractors, extraordinary levels of complexity and contracting requirements are being put in place that bind us to the original vendor for even the most basic forms of service and maintenance. Yes, you can go online and download the software to see the same diagnostic information about your bristling-with-silicon-chips car as the dealership you bought your car from, but no, you can’t do anything with that information yourself. Car dealerships make most of their money from servicing, not from the sales of cars.

The fact that we are so enmeshed in such complex, keep subscribing or lose it, everything from everywhere networks makes it difficult for us to meaningfully change our contribution to the harm our ‘civilisation’ is doing to the planet. If our shoes wear out, how many of us are capable of creating an acceptable form of footwear to replace them ourselves?

We can and should say no to the global supply chain supplied single use coffee cup, plastic fork or drinking straw. But in the words of the late David MacKay:

‘If everyone does a little, we’ll achieve only a little’

Unfortunately, to move beyond achieving only a little we need decisive political action rather than poorly coordinated efforts of individuals or groups who don’t have their hands on the levers of power. The single use drink container has become a community habit. It is unfair to ask a coffee vendor to ‘do the right thing’ when their competitor down the road is not. If single use containers were banned outright, the commercial playing field remains fair.

From takeaway coffee cups to coal fired power station policy we are hampered by the extent to which our principal political actors are enmeshed with powerful elites controlling or benefiting from the global everything for everywhere networks that supply us. The anaemic outcomes of COP 26 exemplifies this enmeshment. We are facing the fight of our lives with at least one political hand tied behind our back by elites benefiting from maintaining the unsustainable status quo. The COP 26 loopholes for fossil fuel use are perhaps the clearest illustration of this.

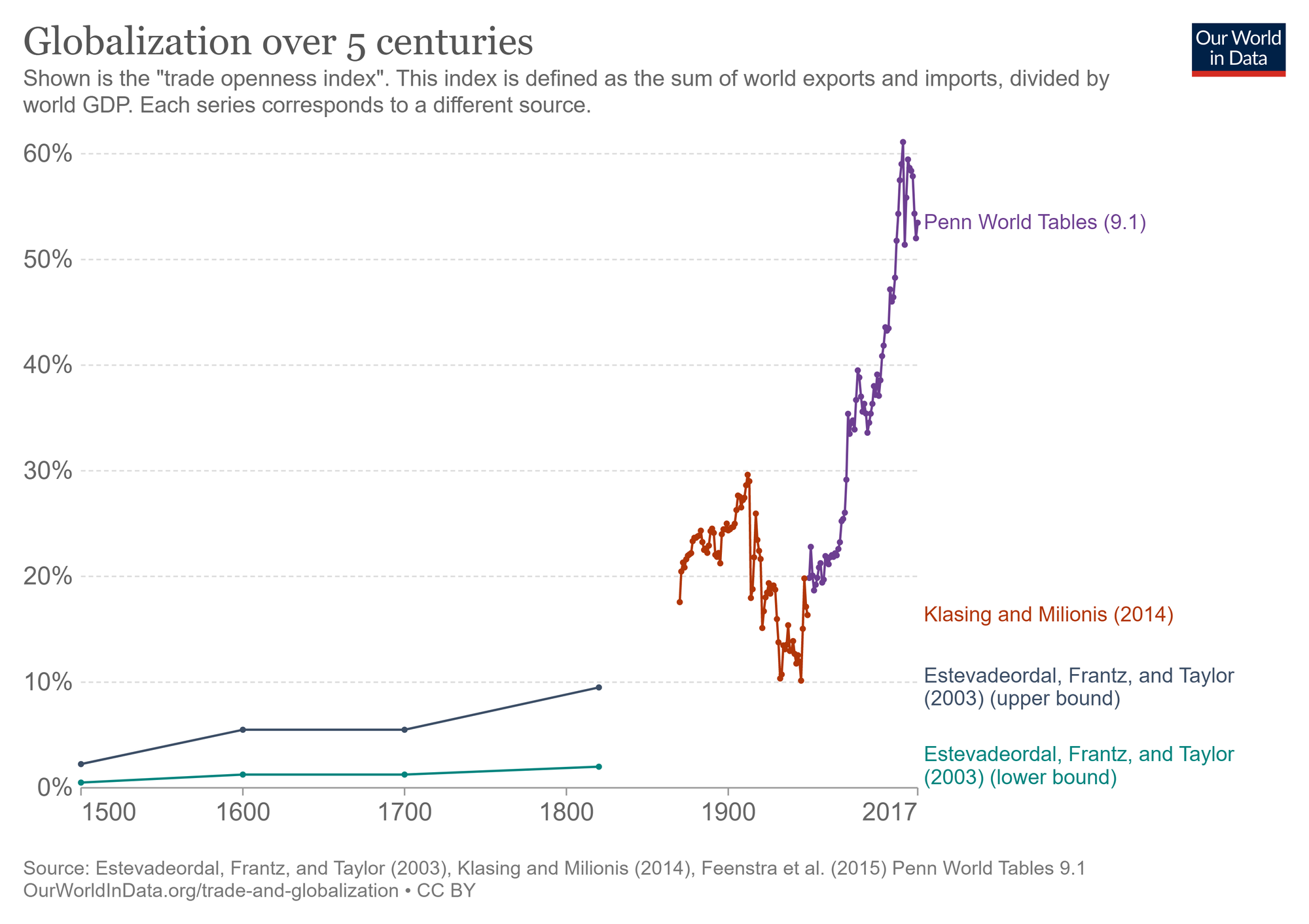

However, there is some good news - well, in a way - about our level of enmeshment in everything from everywhere globalisation. Important metrics of globalisation have actually been trending down since the mid to late 2000s (figure below).

Trade postures are stiffening and tariff barriers are rising. And more recently, the COVID pandemic has compounded generally weak global economic activity. As the pandemic subsides (?) and the world reopens (anyway), overt geopolitical tensions and genuine logistic constraints are decisively turning the tide against unquestioning offshoring of skills and manufacturing to the cheapest location, wherever it may be found on the planet.

Next, as peak everything is increasingly recognised, particularly with respect to energy supplies, resource nationalism can be expected to increase. The sequestering of critical resources for within-nation use will likely stress supply chains beyond breaking point. High natural gas prices in Western Europe this winter are only the beginning. Formerly global trade networks can be expected to regionalise and simplify as a consequence of ‘all of the above’ trends acting against them.

Delays and intermittency in supply or the complete loss of access to goods and services we currently take for granted will become more common. We will need to think carefully about which everything from everywhere things are genuinely important to us and to what extent we are prepared to go to in order to ensure access to them. Perhaps the machines to make the machines to make things locally are more important than the latest consumer product fad. And perhaps also the skills and knowledge to harness those machines.

Clearly, there are a lot of dimensions to the transition to a more regionalised, less well-supplied country, economy and life. I will begin to discuss these in a new 'Less' thread I am commencing with the very next post.

In the meantime, the logic of everything from everywhere we have enjoyed for the last half a century or so can be found in the story of a humble Argentinian pear’s journey to the supermarket shelves of California. Everything from everywhere, at least for a brief period in the seven thousand year or so span of human urbanisation, really did seem to make perfect sense!

Subscribe to thisnannuplife.net FOR FREE to join the conversation.

Already a member? Just enter your email below to get your log in link.