The Climate #8: Playing with fire

Can our forest ecosystems survive a hotter, drier climate?

The World economy is at a dangerous cross-roads. Damned by crashing asset bubbles if interest rates rise, damned by inflation and political instability if interest rates stay low. Can our economic and political masters navigate out of this mess AND save the planet?

Negative interest rates on savings accounts are a genuine brain f**k. ‘Savings’ accounts that deduct money from your savings rather than paying interest, as is the case right now in Western Europe, demonstrate that the world’s economy is fundamentally broken.

Here in Australia, interest rates are nominally just above zero (typically 0.1-0.5%); but well below the rate of inflation of 3.5%. This means savings here are losing value at a rate of -3.0% per year or more. Forget about actually growing savings or living off the interest.

The purpose of the ‘truthenomics’ thread is to shed light on what has gone wrong with the economy and why there are no easy fixes. This in order to discuss some of the challenges we face in trying to muddle through the next couple of decades without becoming destitute.

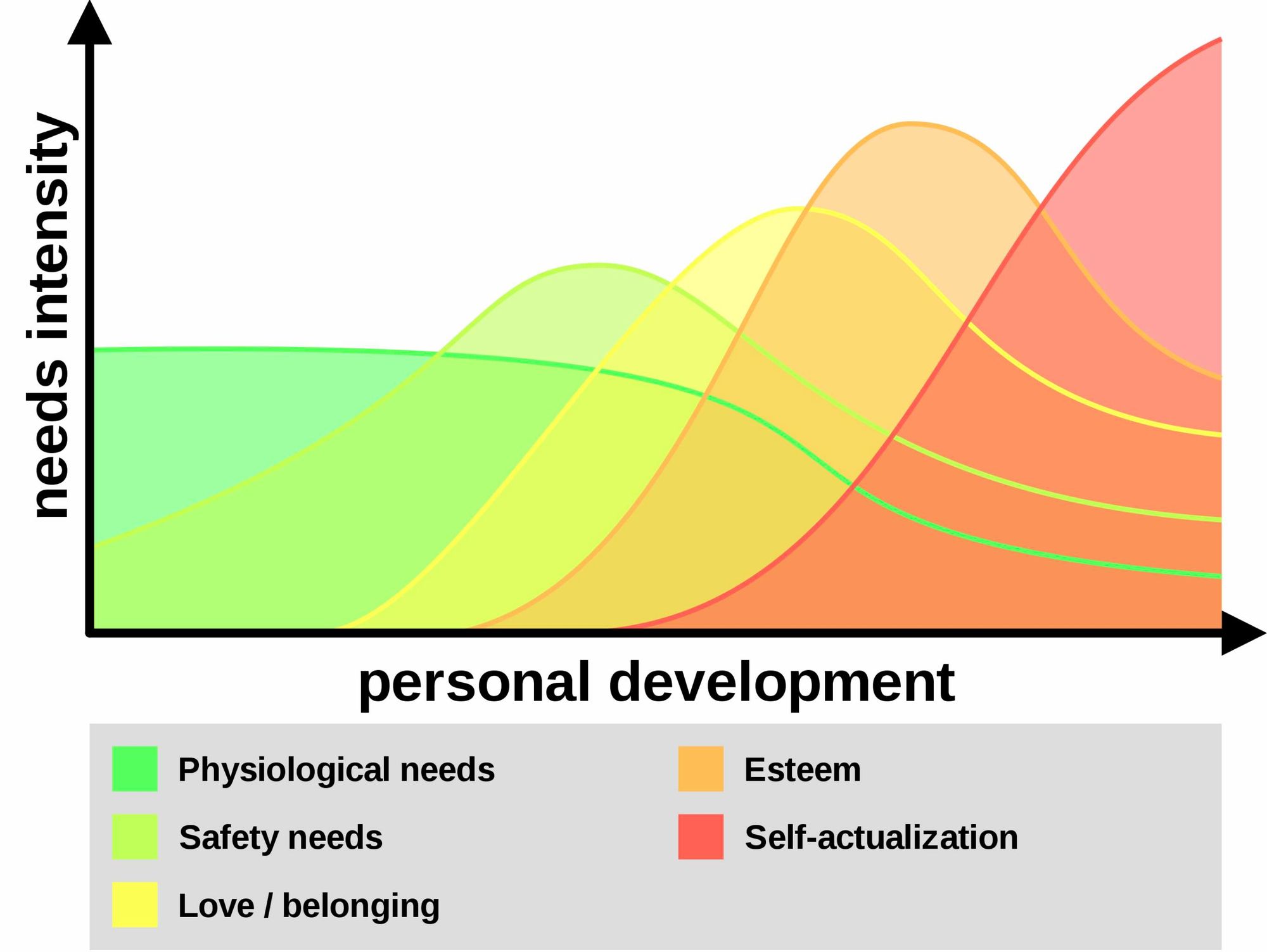

Destitute? Unfortunately, in all likelihood, most of us will be poorer in 20 years than we are now. That is, most of us will be needing to focus more on the life-essential elements of our hierarchy of needs (think food purchases and living somewhere reasonably safe) rather than on more discretionary items (like writing blog posts as a form of self-actualisation).

So, why it is likely most of us will be poorer?

The principal driver is discussed in my initial Peak Everything post. Over the last century, the relatively prosperous lives of the Global North’s middle classes have been supported by very faithful and hardworking ‘slaves’ in the form of coal, gas and oil. Most of us underestimate how important these slaves have been.

For example, trucks capable of carrying a 400 tonne payload and powered by a 400 horsepower diesel engine are quite commonplace in the world’s mining industries. These engines generate the same hauling power as 1,500 people. Lifting 400 tonnes of iron ore 100 metres out of an open cut mine by wheelbarrow would take an individual worker several years. And the task would hardly be considered a middle class job.

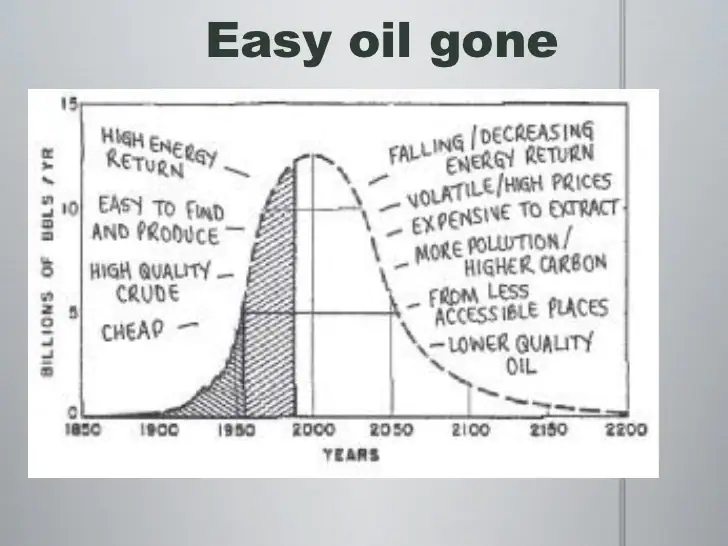

Unfortunately, the era of abundant, cheap fossil fuel ‘slaves’ to do the heavy lifting on our behalf is behind us.

In the early days, only 2 percent of the oil extracted from under the Middle Eastern deserts was needed to extract the next barrel of oil. That is, the energy returned on energy invested ratio (EROEI) was about 50:1. Now, on average, some 15% of the global oil supply is burnt extracting the next barrel of oil. This ratio is relentlessly deteriorating. By 2030 about a third of the fossil fuel energy extracted will be burnt accessing the next unit of energy. By 2040, nearly half of all the fossil fuel energy we extract will be burnt extracting the next unit of energy.

BUT! you must be thinking, won’t we be using renewables by then? Certainly most renewables offer a better ratio than 50%. There is a great deal of debate and different ways of calculating EROEI for different renewables but between 5:1 and 10:1 are fairly commonly quoted figures, similar to what we are getting from fossil fuels at present.

We can’t create a renewables-based energy system (read economy) without continuing to burn fossil fuels to power the transition. And unfortunately, every drop of fossil fuel we use to power the transition leaves less energy left over to power our daily wants and needs.

We are already feeling the economic pinch of being post peak easy energy. Energy shortages have shut down global fertiliser supplies due to manufacturing halts in China. The cost of natural gas is so high in Europe that industries there are facing shutdowns. As usual, it is the poorer folk amongst us who experience the greatest hardship. Indian farmers who can’t afford high fertiliser prices risk starvation. Pensioners in the UK may freeze to death this winter because of ‘rocketing’ energy prices.

Returning to our hierarchy of needs, our economic choices get tougher every year as fossil fuel EROEIs deteriorate. This begs the question: why are we wasting irreplaceable fossil fuel energy powering TikTok or Bitcoin mining rather than conserving that energy to devote to food, heating or the renewable energy transition? Bitcoin mining alone consumes more energy than Argentina (over a third of Australa’s). Central Asian Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are suffering electricity blackouts owing to Kazakhstan's immediate neighbour to the East, China, banning Bitcoin mining. Many miners appear to have just hopped across the border to Kazakhstan and resumed operations there.

Food is close to the top of our hierarchy of needs. Currently, about 30% of global energy production is expended in feeding our nearly 8 Billion mouths. We can push this figure down a little by being more efficient in how we produce food and by making better choices about the food we eat. However, given the reality that we mine food rather than grow it, our energy use choices must change if we wish to keep the world’s population fed. You can’t eat Bitcoin.

It is likely we will need to increase the proportion of available energy to grow food. This is because the resources we extract for our food mining system, like energy itself, are going to take more energy to extract than they do now.

The longer we delay shutting down wasteful uses of energy, the greater the risk of starvation for many. Simultaneously, the longer we delay diverting as much energy as we can to the renewables transition, the poorer those of us who haven’t starved will be, owing to a lack of energy to devote to more upmarket needs and wants than just feeding and warming ourselves.

It shouldn’t come as any surprise that we have ended up in this energy and economic pickle. Human economic behaviour is governed by Lazinomics1:

'When accessing any resource humans always take the easiest to access, best quality resource first and leave the harder to access, lower quality stuff until later.'

Lazinomics applies whether we are collecting wood for a campfire, extracting fossil fuels, mining the raw materials needed for food production or picking fruit from a tree.

Lazinomics also states that: 'We use the early, easy pickings wastefully.' No one was thinking much about car fuel economy before the oil price shocks of the 1970s.

The charade of growth

The bite from our prosperity by the energy burnt in supplying energy is hard to see. In preparing economic reports, all the energy supply activity is rolled up with all other activity that results in a measurable movement of money. Our political masters like to tout the virtues of ever increasing economic activity - so called ‘economic growth’. The assumption being: growing economic activity = growing prosperity. Unfortunately for most of the Global North, the headline economic 'growth' for at least the last decade of a couple of percent or so each year since the Global Financial Crisis hasn’t made people feel more prosperous.

The diversion of effort and energy to maintaining our energy supplies explains this. World food prices have been on an inexorable upward trend for over a decade, doubling in real terms between 2000 and 2020. More spent on food is less available to spend on other things that keep the economic merry-go-round turning. That is, less is spent on discretionary items like a Foxtel subscription or new furniture. But also, rising energy costs mean it is more costly to offer discretionary items as well.

The effect is a vicious spiral where we as consumers have less money to buy discretionary items while at the same time discretionary items get ever more expensive. As a consequence, the economic merry-go-round slows down. Another factor is that older people tend not to spend as much as young families. Governments across the Global North are struggling to maintain all-important economic growth as aging baby boomers spend less and household sizes shrink.

Under normal circumstances, governments rely on either of two tools to stimulate flagging economic activity. Plan A: take from the rich and give to the poor, Plan B: make debt cheaper so all economic actors, us as consumers and companies who supply us take on debt to keep the merry-go-round spinning.

Goodbye to the majority middle class

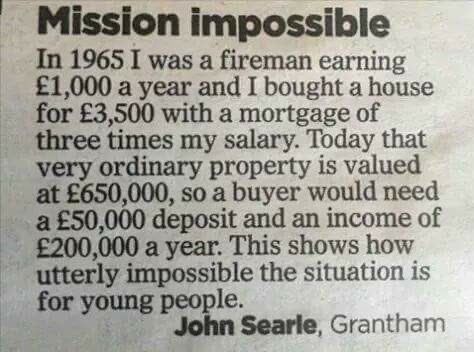

Unfortunately, since the early 1980s, the rich have decided not to play ball with plan A. Social gradients have been steepening across the Global North since then. Taxes on the rich and private enterprise have been cut, leaving less income for governments to redistribute down the pecking order. The lower middle classes in particular are acutely aware that such things as healthcare, higher education and other, erstwhile public services, such as energy and mass transit have been privatised and are taking ever higher bites out of incomes. These bites being well in excess of lower middle class wages growth.

Given plan A isn’t a goer and the rich’s sequestering of wealth has left the rest of us with less money to spend on the merry-go-round, plan B has been put into overdrive.

Interest rates have been cut repeatedly over the last 40 years; finally reaching the absurdly low levels they are now. All designed to encourage us to take on debt and use debt to buy stuff.

Sadly, the debt hasn’t really achieved its goal. The richer have got even richer because the cheap debt has fuelled outrageous bubbles in the prices of houses and stocks (which the rich already owned). And with all that debt going into these bubbles, very little has been left over to spend in the true economic merry-go-round of goods and services. That is, the merry-go-round that is supposed to support liveable income levels for less skilled workers.

The middle classes are being filleted out across the Global North as a consequence. Younger generations, unable to buy a house and in poorly paid, insecure work look with anger and resentment upon retired, comfortably off Boomers. Most are aware a similar prosperous life story is likely unattainable for many of them.

And then governments added more fuel to the wealth inequality fire when the COVID Pandemic hit.

The merry-go-round slowed severely when COVID lockdowns commenced. Plan C, usually reserved for absolute catastrophes - print new money and give it to people to spend - was enacted. Unfortunately, giving people free money during a time of global supply gridlock merely bid prices for available goods and services higher. That is, price inflation, a sleeping destroyer of the effective value of a worker’s take home pay and their life savings was awoken. In the USA, a worker on the same rate of pay now as in 2020 has lost one dollar in 10 of the dollars they take home in purchasing power.

No Plan D

Unfortunately there is no easy way to back out of the mess of massive debt, increasing inequality and asset bubbles of every kind. Getting serious about inflation means pulling excess cheap money out of overinflated assets, likely crashing real estate and stock markets.

Not getting serious about inflation means large sections of the population will no longer be able to buy essentials at the very base of their hierarchy of need: food, energy for heating in cold winters, fuel for transport and cooking. Such privations, when severe, forment bloody revolutions (eg France, Arab Spring). The Chinese Communist Party understands the existential threat to their power that food shortages could cause. Their response? Hoarding and stockpiling over sixty percent of the world’s supply of grains over the last year. Aided and abetted by the Global North's food wastage and selfishness, this hoarding has contributed to food price rises, decreasing food security and exported civil unrest elsewhere round the globe.

Global North democracies are not immune to the political threat posed by widening inequality and increasing inflation. Severe inflation, even without major shortages, can see countries lurch to authoritarianism. Think Germany in the late 1920s/early 1930s.

Meanwhile, truthenomics is neglected

While our focus is diverted by the gyrations of stock and house prices or headlines about polarised politics, we fail to focus on the most important economic bookkeeping we need to undertake. That is, measuring and managing the draw down of our most critical assets (eg the natural resources upon which all life and our economic systems depend) and the rampant growth in our true liabilities (eg atmospheric CO2, global heating, overshoot).

This disconnect means we are likely to overestimate our capacity to muddle our way through ‘all the above’ and underestimate the severity of economic and political shocks we will experience over the next decade or two.

On the plus side, piecing the economy back together will provide opportunities to genuinely change course and reconsider what terms like ‘prosperity’ and ‘a healthy economy’ really mean. Discussing how to plan for and make best use of these opportunities will be the subject of further truthenomics posts.

I will finish with a metaphor for many governments’ current plans to tackle inflation by 'giving up' a reliance on debt. Time will tell whether they (and us!) fare better than Steve-o…

Footnote

Subscribe to thisnannuplife.net FOR FREE to join the conversation.

Already a member? Just enter your email below to get your log in link.